The Finalists’ Exhibition of Mario Merz Prize

Fondazione Merz

2022.6.9 – 9.25

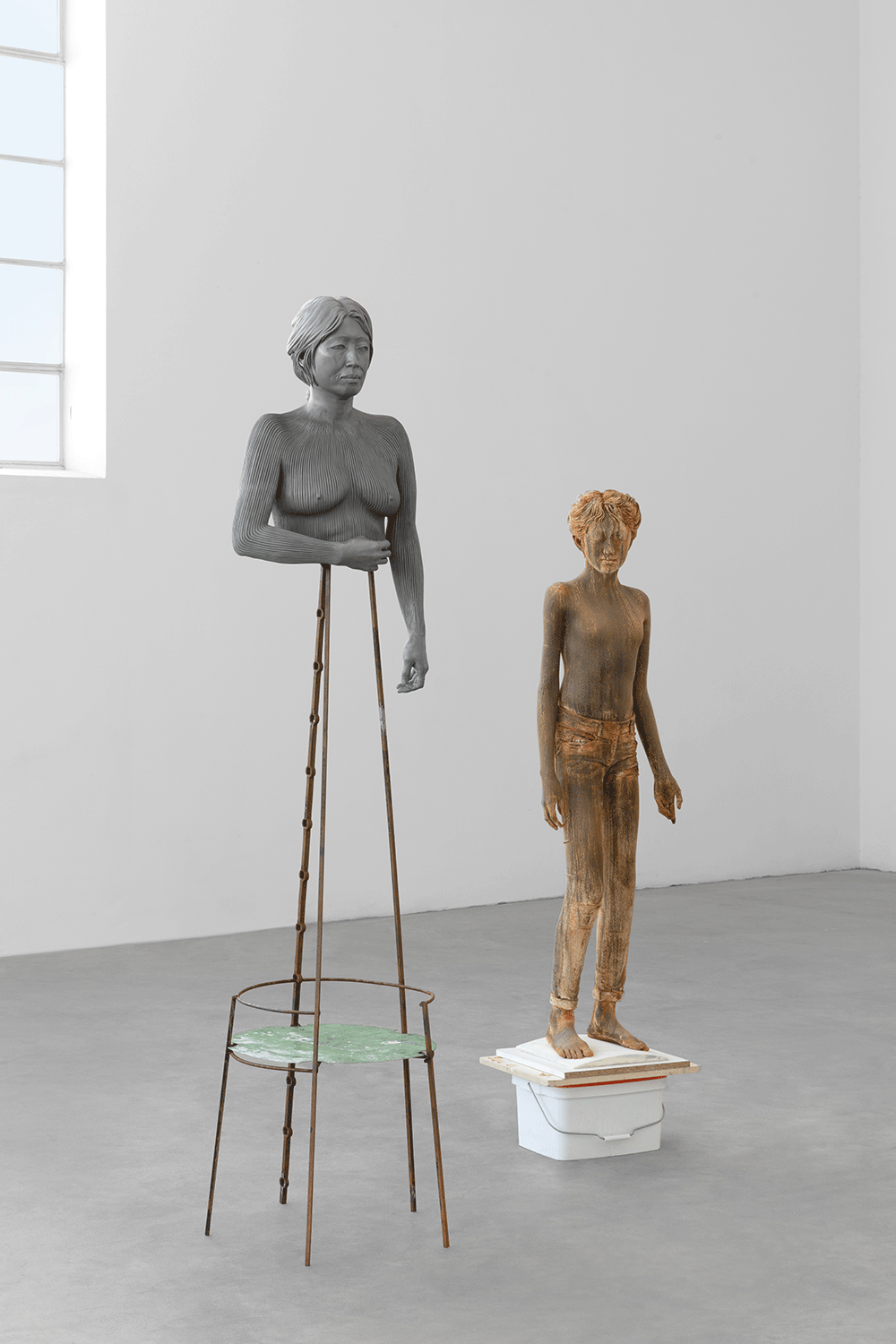

Since He Xiangyu’s sculpture Asian Boy (2019-2020), the artist has continued an Asian theme with a series of sculptures based on his close connections in Berlin, the city where he resides. He feels connected to his fellow expatriate friends and feels compelled to document them through art. Through this body of work, he attempts to reflect the depth of individual bodies and minds throughout the breadth of history, while also giving material and technical know-how an independent symbolic meaning.

The original motivation for sculpting statues was to worship the concept of corporeal immortality as a coping method of the fact that every breath, every endeavor towards achievement and immortality inevitably leads to fatigue and death. The visual disparity between the statue and a real person, on the other hand, renders the statue irreplaceable by a “genuine” image, such as a photograph. The ambiguous image of the real versus that of the unreal, is closer to immortality than the extremely genuine image. Perhaps we subconsciously believe that if an image appears “too genuine” it will eventually fade away. He Xiangyu’s early sculptural works, such as Death of Marat (2011) and My Dream (2012), represent and investigate the classic contradiction between the oppositional nature of figurative sculpture and its desired manipulation of the viewer’s consciousness.

Perhaps for this reason, there was no obsession with figuration in the history of ancient Chinese art as there is in Western culture. For example, in ancient Chinese literati painting, precise representations were never the artist’s goal. Arguably, the tradition of images and their interpretations in Chinese culture is extremely abstract in its pursuits, aiming more at evoking ideas of spirituality rather than focusing on images of concrete objects. Ultimately, the creation of statues to elicit specific emotions and memories is an assertion of power over specific memories, which in Chinese artistic tradition does not need to be conveyed through images. He Xiangyu naturally incorporates this particular Chinese image tradition into his figurative sculptural language in the new sculpture series. The figures embody the model’s individuality and their unique emotional connection to the artist himself, while the underlying subtle non-figurative interpretations project this individual experience onto a broader spectrum of Asian communities.

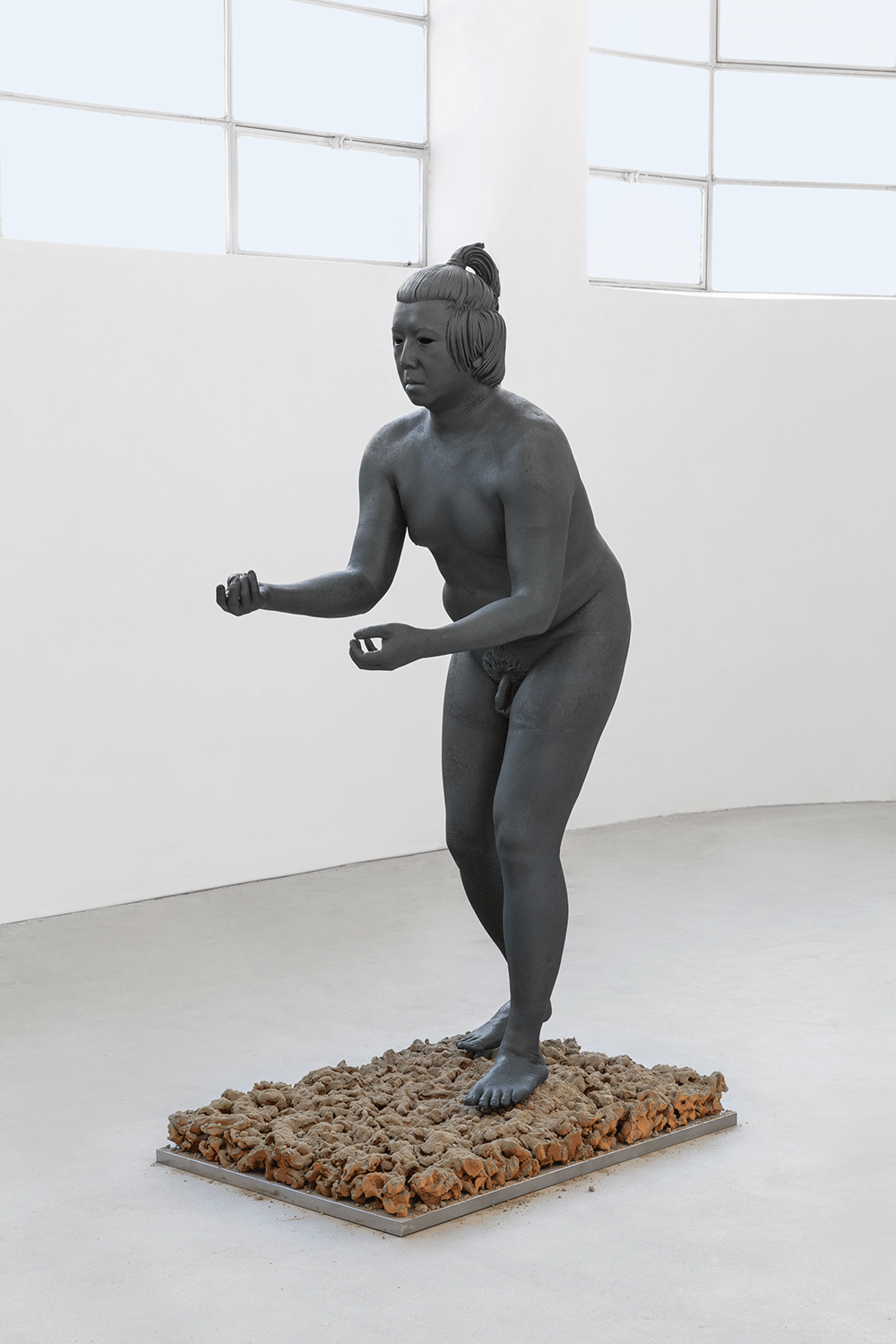

Darryl (2021), similar to other works in the series, is cast from the body of the artist’s close friend, a young man of Chinese descent who was raised in San Francisco and now lives in Berlin. The artist chose the traditional silicone molding process over the more conventional method of 3D scanning and printing, to create the mold from a living person. The uncomfortable physical pressure on the model’s body during the exhausting molding process, in turn, endows the sculpture’s limbs with a transcendent grace:as the molding and casting process transforms positive and negative space, heaviness is then converted into lightness. The paradox is that through the uncomfortable process itself, where the body which has become invisible in the repetition of daily experience and overly familiar perception, begins to reveal itself again to the model, and eventually to all viewers, while simultaneously representing the physical experience of the sculpture in conflict with itself. This contradiction is rarely found in Christian iconography, which frequently employs the vivid image of the Savior’s suffering to elicit introspection and repentance from the faithful. Whereas, in Eastern iconography, the saints’ appearance of suffering consists of compassionate peace. Such a visual tradition is undeniably implicit in Eastern philosophy. Perhaps due to the philosophical difference, or the short timeline of the history that humans have to reconcile this difference, the dilemma of Asians, particularly Asians in diaspora, has always been fundamentally related to this invisibility and the internal and external resistance suffered in the pursuit of acknowledgment. Darryl’s outstretched hands present a gesture of offering and receiving, but the deliberately blurred expression casts doubt, reflecting the unknowability of the response to this gesture. Unlike Asian Boy, the completely naked body of Darryl appears to be distinct from Eastern iconographic tradition, while attempting to bridge the gap between Greek and modernist sculpture, this results in symbolism reminiscent of a coat of arms and concurrently, a realistic fragility. This trait pervades He Xiangyu’s new sculpture series, representing an example of this identity group outside of any specific historical narrative.

Yuki, who was born in Wuhan, China, currently studies design and works part-time as a model in Germany. In 2014, Yuki began documenting the various stages of her life with tattoos and has since accumulated approximately fifty, including one of her puppy Nico that she adopted during the pandemic. Yuki has transformed the various phases of her life and thought in an intimate way by incorporating these tattoos into her body’s memory through an indelible method. Living in Berlin for three years has given Yuki a profound attachment to the city, where she learned how to be prudent and independent, and to be more open and energized by its diverse cultures. Lola, the artist’s long-time friend and studio manager, has lived in Berlin since 2003 and believes that the city has provided her with unique experiences and energy for life. Despite the fact that Lola has visited many European cities over the last decades, Berlin is the only one that gives her a sense of belonging which she attributes mainly to the birth of her daughter, Mia, who was born in Berlin, in 2010. Lola’s life currently reflects the traces of two cultures, the freedom to speak without fear and a nostalgia that is difficult to relinquish. Although her roots have become unattainable, now Lola’s home is where Mia is.

The Elephant (2021-2022), adopts both the typical biological characteristics of the Asian elephant and the symbolic image of the elephant in ancient Chinese statuary, particularly dating back to the Han dynasty. Standing high on the giant elephant’s back, the figure of Mia (2021-2022), the young girl of Chinese and German descent, has slightly closed eyes and does not cast her gaze into the distance as a viewer would expect. Her two hands concurrently form a grasping motion, but also a searching one. There appears to be some hesitancy and confusion—she could be a conqueror and a master but takes on a role that surges into this position. The elephant is a dualistic symbol in Chinese culture. On one hand, it represents an archaic and savage nature but on the other, the taming of savagery implies a great civilizing power, making the tamed elephant a symbol of supreme power and strength. Unlike other beasts, the elephant is seen as both humane and extremely violent, implying that it has a powerful ego comparable to that of humans, and that taming the elephant is also the ultimate example of taming an alien force. Furthermore, unlike the lion and tiger whose images are interpreted directly as symbols of power and force, the image of the elephant is interpreted through substitution. Elephants are a symbol of power, presupposing their being tamed and controlled, and what they symbolize is not their own power but the power of their controller. This metaphorical power lies not in how strong an elephant is but in how strong the reins are and how powerful the harnesser is. Frequently appearing in statues as a solemn and docile figure, the elephant seems to have invincible power but never ventures beyond the threshold. The elephant beneath Mia’s feet is noble, peaceful, and quiet, just like every other elephant tamed by emperors or warriors throughout history, and the long line of history woven out of the fates of the countless living and deceased that elephants have guarded.

“He Xiangyu investigates social and art mechanisms, as well as belonging and consumerist idolatries through irony, while proposing a symbolic revolution which of consumerist references and priorities.

In his practice, He Xiangyu (Dandong, China, 1986) reflects on his upbringing in post-Socialist China. Part of a generation of artists who have experienced first-hand the cultural and economic transition of modern-day China, he uncovers the contradictions between individual existence and socio-political norms. In his projects, which are divergent in form and aesthetic, Xiangyu tackles anthropological, social and political themes to question the institutionalisation of contemporary art, while at the same time addressing the political and existential crises which afflict the world. The body is central and essential in his practice. It becomes the coffer in which to hide the marks of history – of that which is collectively repressed and of current cultural tensions. Thanks to Xiangyu’s ability to translate the history of his country into symbolic images and materials, the viewer gains greater critical awareness of the themes the artist addresses. Conceptual rigour and emotional value are constants which allow the artist to conform complex and universal themes, while avoiding simplifications, probing instead their cultural, historical and ideological implications.”

Written by Giulia Turconi