Food is inherently political: who it represents, how it’s shared and how it’s produced. Across Moana-nui-a-kiwa plantations of copra, cacao, sugar, pineapple and vanilla have been the basis of multiple waves of migrant and slave labour trades, including colonial empires turning to Asia as a labour force. Guangdong Province, which now holds a lead position within China’s economic powerbase, was one of the major ports of exit for often indentured labourers in the early 19th Century.

While the connection of Indigenous communities and Asian labour migrants initially came through colonial plantations, long-lasting relationships formed outside of this imperial canon. Colonial attitudes towards indentured labour changed at the start of the 20th Century and ceased for good in Fiji in 1920, and 1931 in Samoa and Hawaiʻi. At this time many labourers returned to their various homelands, while a significant number decided to settle in the islands long term. Fiji and Samoa went on to gain independence toward the end of the century while Hawaiʻi is still illegally occupied.

Food is one signifier of these migrant and Indigenous relationships. In both Hawaiʻi and Samoa staple diets changed through the introduction of new Asian food technologies, such as noodles, rice and pastry. Foods such as sapasui, keke pua’a and musubi borrow from these new technologies, becoming local delicacies. Moreover, these highlight the power indigenous people have to adopt and adapt new food in their own diets, a sovereignty which doesn’t always exist in colonised lands across this vast ocean.

As descendants of Samoa, Fiji and Hawaiʻi that have grown up in Aotearoa we (Lana Lopesi and Ahilapalapa Rands) are implicitly connected to this history with our respective homelands having been administered by Germany, Britain and America respectively.

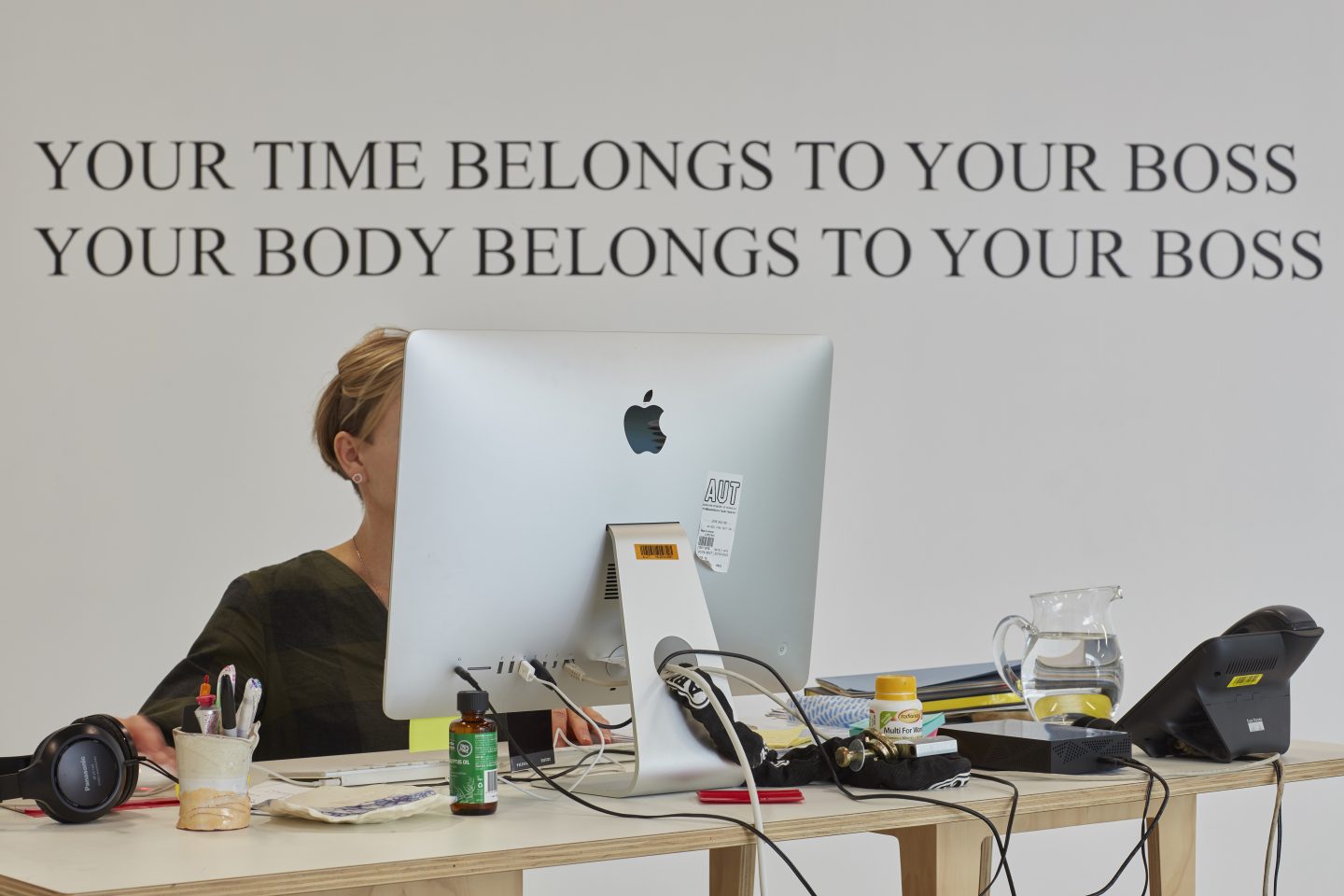

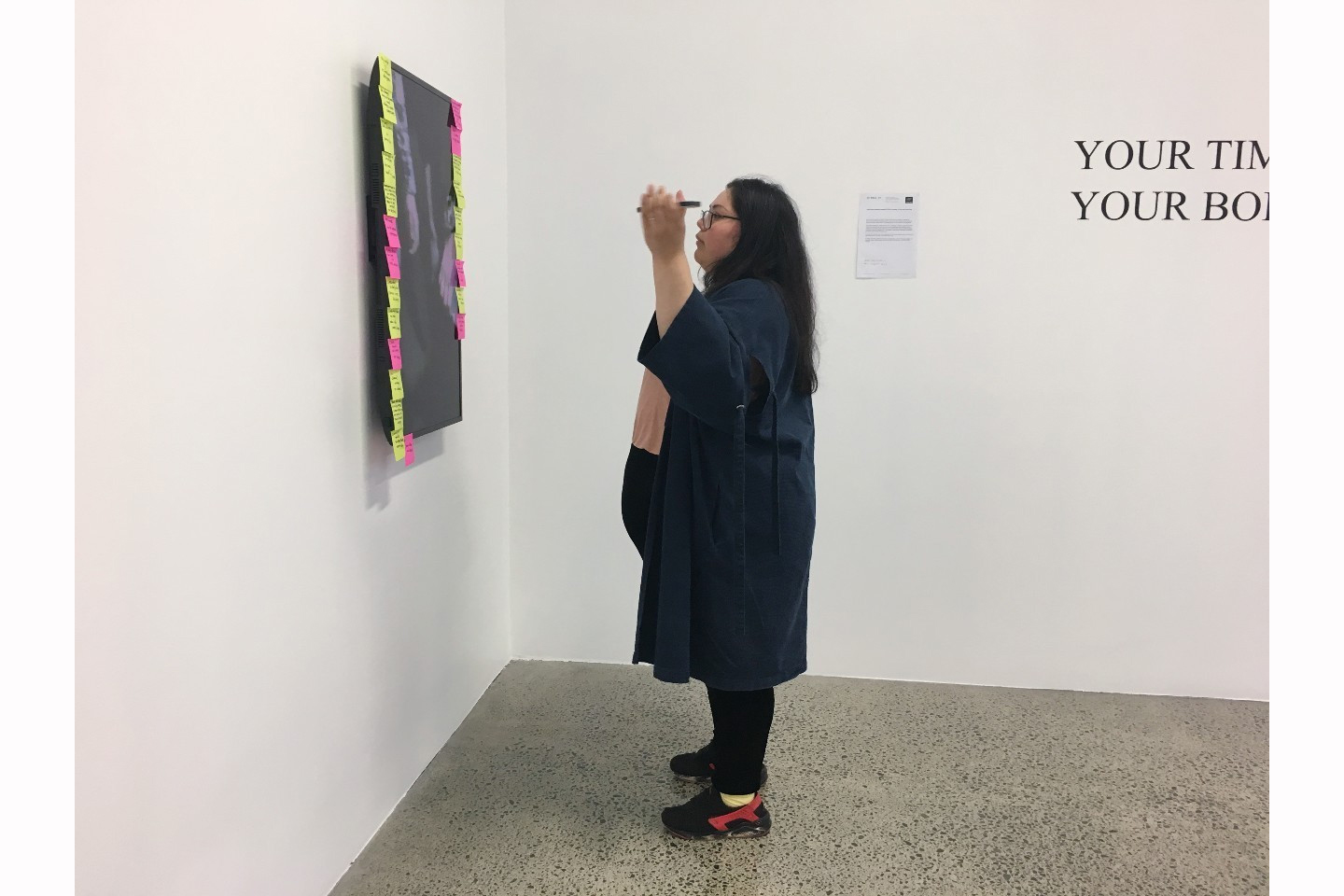

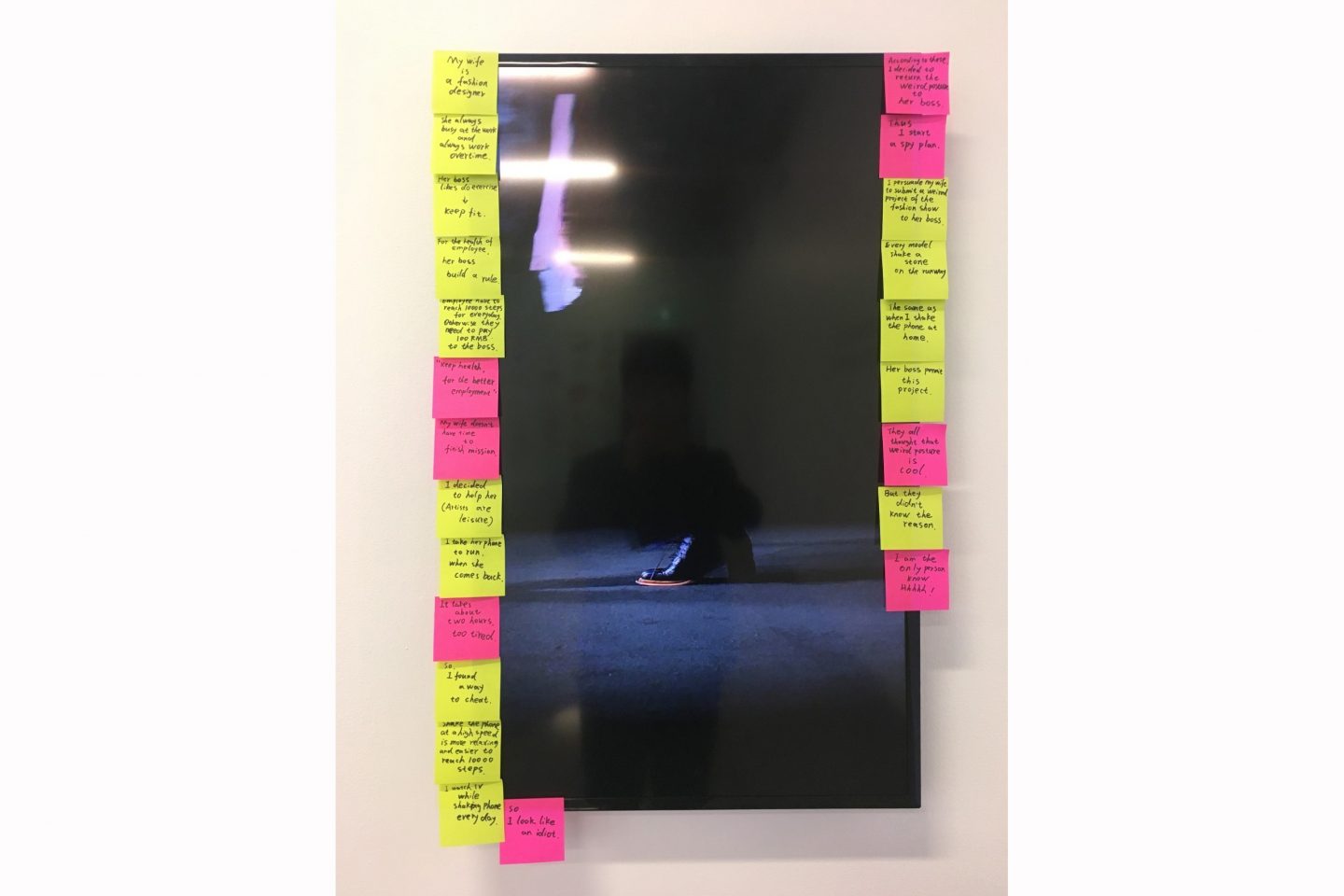

The plantation is a site where we not only cultivate crops but also trauma, resilience and hybridity. Through a variety of artistic approaches lei-pā uses food and labour to open up conversations of historic and contemporary cultural exchange. The artists featured in this exhibition speak from their context within both China and Moana-nui-a-kiwa. Their works are broad ranging, drawing upon the production of food and food sovereignty to highlighting the labour required within our capitalist global market.

Poking fun at the systemic foundations of nation states and critiquing international economic relationships masked by diplomacy, our narratives are not tidy, but it is where the works intersect, connect and miss one another that some semblance to our lived histories is honoured. We are so often pitted against one another within a politics of scarcity. However, through shared traumas of sorts, we can bypass the empire and talk directly to each other, as we have been doing for thousands of years.