We are delighted to announce that Vajiko Chachkhiani’s first solo exhibition, “Finger, Fist, and Thumb Sucking” at White Space, opens on Saturday, September 17, and will run through Thursday, October 27, at the Shunyi location. The exhibition is comprised of his recent sculptures, paintings, and video.

“Finger, Fist, and Thumb Sucking” is a narrative about the psychological transformation of an individual’s life journey, the search and affirmation, revisiting and bidding farewell to the self. The exhibition’s title refers to the three gestures of the hand as a reference to the basic desires inherent in every child while alluding to notions of security and violence, rejection and acceptance, dependence and independence, the true self, and deception shaped and acquired from later life experiences.

In the first half of the exhibition, the spectator will enter a sculptural complex that resembles a children’s amusement park. Based on the shapes of his own children’s favorite toys, the artist has created sculptural pieces much more prominent than conventional scales, exploring “toys” as objects and how the mechanisms behind the act of playing with “toys” (games) shape the relationship between the self and the world at an early age.

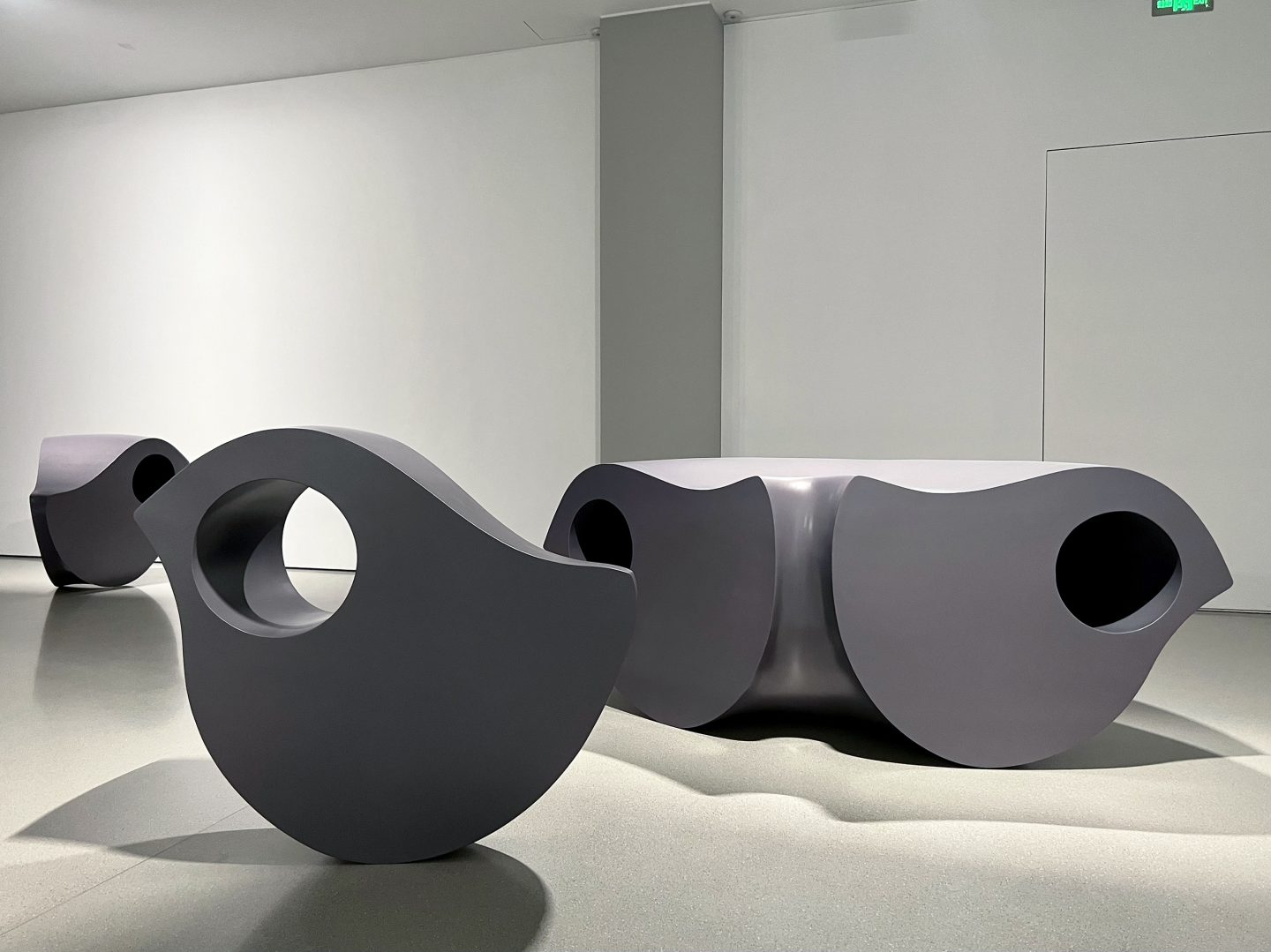

The First Possessions and Not-Me Possession are a series of large owl-like and bird-like sculptures whose playful forms and expressions mix joy and surprise, their uncanny mouths, and eyes wide open to form long passages as if inviting children to explore them. The work invokes the concepts of “transitional objects” and “transitional phases” from psychologist Donald Winnicott’s Playing and Reality, which refer to the intermediate stage and intermediate object of the infant individual as they leave the care of the mother and establish the self, establishing one’s inner world and the broader external world. The “first possession” comes from the child’s discovery in play rather than being given or imposed. Such findings and choices made by the individual child also mark their first creative and artistic experience.

If the choice of toys and play represents a child’s free will and how they relate to the outside world, conversely, adult control over toys and play can become a form of discipline for the child. The animal-shaped rocking chair sculptures Do This and Do That and Don’t Do This and Don’t Do That scattered throughout the gallery extend the exhibition’s discussion on the systematic influence of education and culture on child development. The small rocking chairs swing freely; for other oversized rocking chairs, chains not only confine their swinging directions but also make them appear dangerous from tipping over.

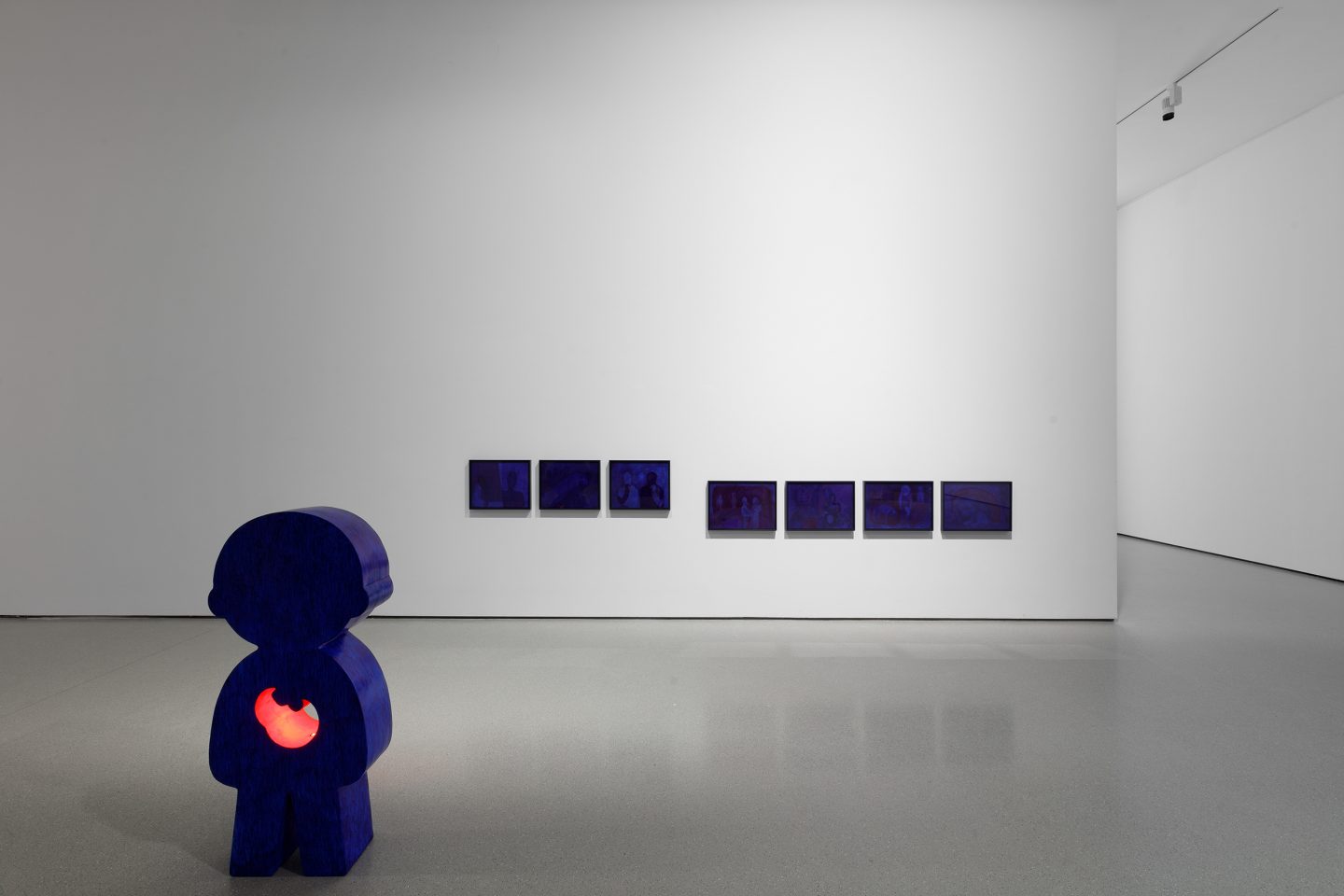

Playing with toys is more than an individual act; it can also be a group action involving competition. In the series of sculptures, We Are in The Circle But You Aren’t, the artist explores the sources of violence and bullying among children and questions whether violence is human nature or an acquired experience. The work appropriates the forms of carved wooden toys from Waldorf Education, the world’s largest promoter of the alternative education movement. Based on the teachings of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophy, Waldorf Education emphasizes the importance of imagination in the learning process by integrating values in academic, practical, and artistic pursuits. It has been controversial for promoting religion, spiritual content, homeopathy, and potentially racist teaching. The blue marker strokes painted all over the work look like a downpour of night rain, making the children seem quiet, silent, and detached. The crescent-shaped flame alludes to Francesco de Goya’s painting Witches’ Sabbath, suggesting manipulation from politics, religion, capital, etc., on people and their inner fear.

In the second part of the exhibition, the artist explores the connection between childhood experiences, individual and collective memories, trauma, and the adult individual with the film, The Warm Winter Sun. The piece portrays a middle-aged man returning to his childhood home in the countryside, whose empty home still retains many details of his past life, bringing back vivid memories. After a brief reflection, the man burns down the house to the ground, a powerful ritual of bidding farewell to the past. However, does such a destructive act allow for self-reconciliation and regaining freedom, or does it re-enforce past wounds? After the man leaves, the ashes will nevertheless remain with him forever.

The-First-Possessions-XS,2022,不锈钢-stainless-steel,125×53×111h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)

The-First-Possessions-S,2022,不锈钢-stainless-steel,125×105×111h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)

The-First-Possessions-X,2022,不锈钢-stainless-steel,197×130×102h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)

The-First-Possessions-XL,2022,不锈钢-stainless-steel,254×130×95h-cm.png)

-We-Are-in-The-Circle-But-You-Arent-The-Night-is-Full-of-Stars,2022-1440x2160.png)

-We-Are-in-The-Circle-But-You-Arent-I-Am-Not-Scared-But-Still-I-Feel-Something-in-My-Belly,2022,木头,LED灯,艾迪马克笔,丙烯-wood-LED-light-edding-marker-acry-1440x2160.jpg)

-We-Are-in-The-Circle-But-You-Arent-Please-Wait-For-Me,2022,木头,LED灯,艾迪马克笔,丙烯-wood-LED-light-edding-marker-acrylic,61×20×119h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)

-We-Are-in-The-Circle-But-You-Arent-I-Can-Walk-Through-The-Forest,2022,木头,LED灯,艾迪马克笔,丙烯-wood-LED-light-edding-marker-acrylic,56×16×99h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)

-We-Are-in-The-Circle-But-You-Arent-Short-Shadow-of-A-Tall-Tree,2022,木头,LED灯,艾迪马克笔,丙烯-wood-LED-light-edding-marker-acrylic,49.5×16×86.5h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)

-We-Are-in-The-Circle-But-You-Arent-,2022,木头,LED灯,艾迪马克笔,丙烯-wood-LED-light-edding-marker-acrylic,38×16×81h-cm-1440x2160.jpg)